Jon Scheve with weekly market commentary made on August, 19, 2022

Ukraine Highlights

Under the new export agreement, over the last 18 days Ukraine loaded over 25 vessels averaging nearly 25,000 tons each, which means exports now total just over 625,000 tons this month. The Ukrainian government’s goal is to load 3 million tons per month, so they are behind. Even if the pace or load size of the vessels increased to their goal, moving 3 million tons per month is not enough to move all the remaining 2021 harvested grain still trapped in Ukraine a year from now. That means there is uncertainty over where the 2022 harvested grain will be stored over the next 2 months, let alone when the new crop will ever be exported.

There are also concerns about how much winter wheat will be planted in the next two months in Ukraine. There is even concern about how much wheat gets planted in the United States during this time because of high fertilizer values.

The market seems to have put these concerns on the back burner, but that does not mean they have gone away.

Basis Vs Spread

I was recently asked how I could claim the basis level I traded in March for April shipment against the July futures was the highest of the year for my farm when the posted basis values this past month were so much higher. This is a great question. Following provides some context.

The September Futures Contract Is Not Really an Old Crop Contract

Most basis bids are currently against the September futures contract. Recent market discussion around the high US basis values has some in the trade suggesting this could indicate a corn supply shortage. However, I think this is a flawed theory because it is based on September futures being a viable contract month for the industry to use as a physical trading tool, like the 4 other delivery contracts of December, March, May and July. Since the September corn delivery process overlaps the early harvested corn, it leads to a logistical problem.

For example, physical sellers of September futures have until September 14th to load barges or train cars. It then usually takes another 7+ days for buyers to acquire the physical grain, which would be around September 20th. This coincides with harvest reaching central Illinois, Iowa, and Nebraska. Plus, newly harvested corn from the southern crop can meet end user needs until harvest is in “full swing” throughout the rest of the US, about 10 days later.

That is why the September futures contract is not like other contracts on the Board of Trade and is generally unreliable for most of the trading industry to secure corn in tight crop years. It also explains why the September contract basically follows the December new crop contract. And, if the September futures contract cannot rally, basis must do all the work.

So, while basis levels may look good against September futures now, they should be compared against the July futures that are no longer trading for a better comparison.

How To Compare the July / September Futures Spread

To compare contract months, it is best to look at prices the week leading up to the July delivery period when end users begin switching bids from the July contract to the September. This year, most end users switched their bids between Monday, June 27th and Wednesday June 29th, when after the close the July futures went into the delivery process.

The chart below shows the July / September spread went from 80 cents inverse on June 27th to 115 cents on June 29th, right before the delivery period began.

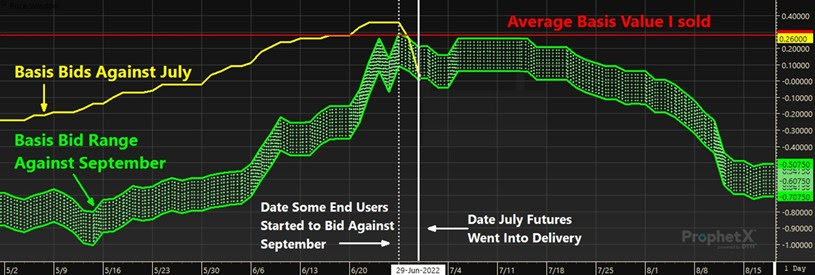

Following shows the average basis values against the July (yellow line) of several end users near my farm over the last several months. The green lines represent the range for those same basis value bids, but against the September futures and accounting for the July / September range at the end of June.

To explain further, on June 29th when July futures were $7.70 the September futures were $6.64 (a $1.06 spread inverse). The basis bid against the July that day was +35 cents, making the bid a cash value of $8.05. With a cash value of $8.05 and then looking at that bid compared to September futures at $6.64, this meant the basis bid against September was the equivalent of +1.41 on the same day.

On the next day June 30th, the posted basis bid, now against the September, was +1.21. This may look like a higher basis value than the +35 against the July the day before. However, after accounting for the July/September spread difference, the now $1.21 basis bid was actually 20 cents lower than the basis bid the DAY before.

Almost every market throughout the US saw this 20-cent basis decrease on June 30th. It was basically a huge basis drop hidden in plain sight, because most grain sellers focus on cash values and did not recognize the futures spread difference from the day before. For an easy rule of thumb, subtract 100-cents from any posted bid against the September to compare it to the July.

As the chart above shows, since June 30th basis values against the September are consistently lower than bids against the July contract. There were only a few exceptions in the main growing areas where basis values where higher than July, after accounting for the spread. These locations were those that likely had rail logistical problems from early summer purchases not arriving on time.

Comparing The Basis Level I Sold

The red line in the chart above represents the average basis value I sold, picked up on my farm in April and May, against the July futures for 100% of my crop. This was explained in detail in previous newsletters.

Posted basis values only went 10 cents higher the last week of June (yellow line) from what I sold. However, that does not account for the interest savings I received moving my grain in early April/May instead of late June/July. With grain valued at $7 and operating note interest near 6%, it costs 3.5 cents per month to keep grain in storage this summer. After interest is considered, I basically matched the best posted value seen for basis near my farm.

As the green section of the chart shows, basis bids against the September contract never surpassed late June values against the July contract, or what I traded.

Basis And Futures Are Not Necessarily Tied Together

Many farmers did not sell their remaining old crop cash grain in June because they thought futures would go up. However, basis and specifically September futures are not tied together, and must be separated. In this case especially, because when the basis increased in June and the spread widened, it clearly showed grain was needed immediately for June and July delivery against the July contract.

Every US commercial storage facility likely took advantage of this opportunity to move any remaining physical grain they owned against July futures back in June. These trades allowed end users to secure enough grain to cover their July needs and likely some of August too. Ultimately, this meant end users only needed to find grain for a few weeks in late August until the new crop harvest in the south started putting pressure on basis values throughout the rest of the US.

This Sounds Very Complex

Inverse markets, where the current futures month is higher than the following month, are very hard to trade and need to be handled differently than the usual carry market in corn. This is especially true of the July/September spread. Inverse markets want physical grain now, even if futures could go higher. That might mean the best approach is to sell cash grain and re-own it with futures or options. Or consider setting basis and waiting to set futures with the buyer at a later date.

This Is a Rare Occurrence; I Don’t Need to Worry About It

Being complacent in an inverse market is a common mistake cash grain sellers make. They think if futures end up spiking $1 per bushel, basis will only fall 10 cents. That may be true in a carry market, but NOT in an inverse market in July and August, which occurs on average about 1 in 5 years.

By not taking into consideration inverse market nuances, farmers could easily take $1 less per bushel on their cash corn. This is regardless of the futures prices a farmer decides to sell, because it is the BASIS that can drop over $1 per bushel during that time frame even if futures go up. The chart above shows basis values have decreased more than 80 cents since the end of June. A farmer still holding 20,000 bushels of corn past June 29th, hoping for a futures rally, has already missed out on $16,000, no matter where futures go from here.

It is important to keep in mind that basis values WILL continue to decline until around October 1st. The chart below shows that the average basis value in my area has already fallen 80 cents since the first of July.

Since the ethanol mandate 15 years ago, basis values in my area have never been above -20 during harvest. That means basis values near me have another 60 cents of downside pressure, regardless of where futures values go. While this chart is for my area specifically, the same thing is happening in every other basis market throughout the major growing areas too.

That means any farmer still holding grain waiting for futures to go higher, and who does not have at least BASIS set against it right now, will continue to miss out on opportunity.

Bottomline

Farmers need to understand how the market works to avoid missing opportunities, because there is little incentive for end users to explain this strategy to farmers since it directly impacts their profits. If your grain marketing strategy does not take into consideration basis and spreads, you are severely handicapping yourself.

Jon Scheve Superior Feed Ingredients, LLC

9358 Oak Ave Waconia, MN 55387 jon@superiorfeed.com

Comments