All About Options on Futures Contracts Part 2

- Wright Team

- Jun 6, 2021

- 21 min read

This is the second part of the article. First part can be found here: Part 1

Lesson Nine: Writing Call Options as a Price Enhancer

On December 24, 2020, the May 2021 $4.40 call had a premium of 30 cents with May futures at $4.51. A December 2021 $5.00 call option has a premium of 15½ cents with December 2021 futures at $4.24½.

What that means to you as a corn producer, someone was willing to pay you on December 24, 2020, 30 cents a bushel for the right, but not the obligation, to buy your corn on a May HTA contract for $4.40 and pay you 15½ cents a bushel for the right, but not the obligation, to buy your corn on a December 2021 HTA contract at $5.00.

You can write those options in your own options account in which case the premium money will be transferred to your trading account. However, you will be opening a short call position, and you will be subject to margin calls.

I prefer those options be written through your grain merchandiser so he is liable for the margin calls. After the merchandiser deducts a service fee, the balance of the premium can be added to the cash price of your 2020 corn delivered early in 2021 or held and added to the price of your 2021 corn.

There is a catch for you: if that call option is exercised, your merchandiser will have a short futures position at the strike price of the written call option and he will assign that short futures position as an HTA delivery contract to you. That is not all bad. You still keep the premium. How bad is it to be required to deliver corn at a $4.40 or $5.00 HTA price?

Before you enter into such a contract, make sure you know:

1) What the call option’s premium is so you do not get stiffed by the merchandiser.

2) What the service fee is for writing the call option through your merchandiser.

3) What various delivery periods the potential HTA can be rolled to and the service fee for the roll.

a) If at all possible, you want to be able to roll that new HTA contract to the next crop year so it does not interfere with pricing the current year’s crop.

Most of these written call contracts are initiated when the futures prices are low and farmers are seeking all the price enhancements they can get. That is a mistake. The futures prices always rally when prices are below the cost of production, the options will get exercised, and the corn producer is delivering additional bushels of corn at prices below breakeven. In April 2020, May corn made a 14-year low at $3.01. A farmer came to me in November 2020 with $3.30 March 2021 HTA delivery corn contracts with March 2021 corn over $4.20. How did that happen? His market advisor wrote March 2021 $3.30 corn calls when corn was near a 14-year low.

Writing call options establishes a ceiling on the price you can receive but does not establish a floor price. Therefore, make sure the strike price of the written option is a profitable price for your operation!

Write these calls to enhance your price when futures are higher than normal, not lower than normal.

I see no reason why everyone of you should not have your grain merchandiser write a December 2021 $5.00 call for 15 cents on every bushel of 2020 corn you deliver in the coming months. Even if the service fee is 3 cents, 12 cents a bushel will be the easiest 12 cents a bushel you ever made. The absolute worst that will happen is you will have to deliver corn on a $5.00 HTA, but make sure you can deliver that potential new HTA corn in the pre-determined time frame.

When was the last time you let someone pay you 15 cents for the right to buy your corn at $5.00?

Lesson Ten: Buying Call Options and Buying Put Options as Price Enhancers

Since no one knows what the market will do, farmers are often encouraged to buy call options when forward pricing their crop. Let’s say in June, a farmer does a soybean HTA at $10.00 to eliminate his down side risk, but he also buys a call option to keep the upside potential open. The calls bought at the same time one prices the crop are often called “courage calls” because the long calls give the producer the courage to price his crop.

I do not like buying calls, and that is especially true when futures are high enough a producer is thinking he should be pricing his production. The worst time to buy calls is when prices are toward the upper end of the annual price range.

Those folks who buy a call option when they price their production contribute greatly to why something like 90% of the call options expire worthless. The second reason so many calls expire worthless is because, even if futures prices rally, it is so difficult to pick the top of any market. Add the human emotion factor of unending optimism (greed) that if prices are up today, they will be up tomorrow and, if prices are not up tomorrow, prices will come back the day after that.

I highly recommend you never buy a call to give you the courage to price your production. Just price the production and, if futures go higher, buy a put option because you know the probability is very high futures prices will decline.

When you price your beans at $12, do you have enough confidence prices will continue higher to spend 20 cents a bushel for call options or does it make more sense to wait and see if futures rally to $13 or $14 and then spend 20 cents to buy a put?

Do futures prices generally go up faster than they go down? How many days do futures prices stay near the high compared to how many days they are close to the low? Let’s look at some charts:

The above chart is 2011 November soybeans. The price was above $14.50 three days, lost $3.00 in five weeks, and then were below $12.00 for eighteen days and below $12.50 for the better part of two months.

The chart below is 2018 November beans which were above $10.50 for 15 days, lost $2.60 in three weeks, and then were below $8.50 for the better part of four months. There are two December corn charts in the following pages. You can easily see the same price pattern in the corn. When the crop gets made, prices fall out of bed.

Lesson Eleven: Sell the Cash Grain, Buy Call Option (Own Grain on Paper)

Most years, the bins need to be emptied before the futures market makes its high for the year. Owning the “grain on paper” means being long the futures market or long with a call options instead of being long grain in the bin.

Simply sell the grain, and then replace those bushels by buying futures or buying a call option. It is great way to vastly improve the cash flow of an operation while maintaining the opportunity to benefit with price appreciation if the futures market moves higher.

The cost of storage is gone. If one buys futures, his futures market risk is exactly the same as if the grain was in the bin. If one buys a call option to replace cash grain sales “on paper,” he will make less with the call than he would with a futures positon, but his risk is limited to what he pays for the call option.

Lesson Twelve: Practical Application of Selling the Grain for Cash and Buying Call Options

Jim has been farming all his life. He is in his early 50’s, and he is a perfectionist and very conservative, especially with his money. He is not “tight” with his money, but he is frugal. He researches everything he thinks might help make his farm more profitable and is really quite quick to adopt new technology because he does his research and gets his ducks in a row before he invests.

He has long known his grain marketing expertise was not nearly as fine-tuned as it needed to be. For years, he searched, read, sought advice wherever possible, which was very difficult to find. There just are not many people whose job is to teach farmers about grain marketing. Nonetheless, the more Jim learned, the more he knew his grain marketing program was really terrible! Our paths happened to cross about four years ago at an auction, and we became friends long before he knew I was a grain marketing consultant.

My clients know I can talk longer about grain marketing than anyone can listen. Jim can listen far longer than anybody I have ever talked to about marketing. He almost wore me out in 2019!

Much of our conversation was how futures and options work. He has often said something like, “Ahhh, so that is why my merchandiser said …” or “That must be what a neighbor does because…”

By early 2020, Jim knew he had to open his own futures and options account to gain the flexibility he needed to improve his grain marketing and cash flow. He knew he only wanted to buy options because that was the only thing he could do in his own account that would absolutely, positively never surprise him with a margin call and it would be impossible to lose more money than he paid for the options.

After milking me for all the information I had on futures and options, Jim explained to his lender, Ashley, why he wanted to borrow $4,000 to buy two July soybean calls. Jim had never traded futures or options, so I was amazed he was able to borrow the money to speculate on the soybean market. His point he hammered home was it was much better cash flow management to speculate on higher soybean prices by owning soybean “on paper’ with limited risk of $4,000 on 10,000 bushels than it was to speculate on the soybean prices with $84,000 worth of beans in the bin with nearly unlimited risk.

Ashley loaned him the money, and Jim opened his futures and options trading account in April, 2020. Since he had just sold his 2019 soybeans, he decided his first transaction would be to pay $2000 each for two July 2021 $8.80 soybean calls to “own his beans on paper.” At the time, the $8.80 call option was 40+ cents out-of-the-money, meaning July 2021 soybean futures were at $8.40, 40 cents below the option’s strike price.

The worst that could happen was Jim would lose $4,000 on the two options (5,000 bushels each). He was remarkably comfortable with that. I was not comfortable with his paying that much money for his first option transaction. His thinking was sometime in the next 14 months, July 2021 beans had to be above $9.20, which was his breakeven price needed on the futures to cover his option cost on expiration day. I could not disagree with that, but to tie up $4,000 was not wise. But as Jim reminded me, tying up $4,000 to speculate on the price of 10,000 bushels of beans was a lot smarter than tying up $85,000 with beans in the bin. I countered with the fact the margin on two bean futures contracts (5,000 bushels each) was only $3,000. As I knew he would, he responded, “Yeah, but then I would be subject to margin calls, and I do not want that.”

On September 12, 2020, with July 2021 beans at $9.95, Jim’s July 2021 $8.80 calls were worth $6,100 each. He had more than tripled his investment in five months; that would be $8,200 net profit on an investment of $4,000. To put it another way, Jim turned $4,000 into $12,200!

Had Jim bought July 2021 soybean futures, he would be long July futures at $8.40 with $1.55 profit on 10,000 bushels, a mere $15,500 of profit. He would have turned $3,000 into $18,500!

I pointed out to Jim he had accomplished his goal much sooner than he expected, and it was time to sell his call options. He did not like that idea.

I was happy for Jim, but his goal was to make 80 cents a bushel. He had done that. Of course, like everyone else on September 12, 2020, Jim thought beans would continue higher and he was not going to sell his call options.

I said, “Jim, you bought these calls when no one except you and I thought beans would go up. It was a great move. Congratulations, but now ‘everyone’ thinks beans cannot go down and you are one of them. Yeah, I am friendly beans, but I have been wrong many times. You did a year’s worth of research, opened a futures and options account for the first time in your life, and speculated on bean prices with borrowed money even though you were scared to death. You invested $4,000 with the expectation to turn it into $12,000. You did it. Don’t screw it up now by changing your plan.”

Jim thanked me for my opinion and said he would wait a little bit.

My fear was Jim would treat these calls like beans in the bin. When the price starts going down, he will hang on because, well, that is what farmers do when they do not have to pay margin calls. Jim knows his broker will never call him for margin money. I think farmers who buy call options to replace cash grain sales are just like farmers with grain in the bin. They have a false sense of security that they will not get hurt in the long run.

Your grain bin never calls you to tell you lost $1,500 yesterday and $800 the day before that and $1,300 the day before that. Call options never inform you how much money you are losing either. Jim could have lost all of his $12,200, and no one will ever say a word to him as the money flows out of his options account.

However, if Jim had bought futures, and the market started falling out of bed, I guarantee Jim would not have let money disappear from his trading account week after week before he pulled the plug on a declining market.

Within six days, Jim’s call options increased in value another $1,100 each. No, of course, he did not sell. That day turned out to be the high day for soybean futures in September.

Jim called me the last day of September. Bean futures had declined 46 cents from the high on the 18th. Harvest was well underway across the Corn Belt, and beans were yielding “better than expected.” Basis had weakened.

Jim asked, “Is there any reason to think that beans will firm during harvest?”

I said, “The seasonal trend turns up on the 10th of October, but the price could easily decline another 40 cents before then. Plus, there is no guarantee that what bean prices normally do after October 10 is what they will do this year, especially since they have already rallied $2 from the low in April.”

Jim replied, “Yes, that is what everyone is saying.”

I reminded Jim, “Usually, when ‘everyone’ is saying the same thing, they are wrong.” Remember, he had said back on September 12 “everyone” thought beans would continue to higher… and they did for six more days, followed by a lower close (closing price) six of the next seven days.

Jim sold his calls that day for about $2,800 less than he could have gotten in the 18th and about $1,600 less than his goal.

By November 21, 2020, July futures were up $1.80 since the day Jim sold his calls. He missed out on about $16,000 of option gain since the end of September.

Sad? Well, yes and no.

Do you think Jim learned a lot about futures and options?

Yes.

Do you think Jim made some good money?

Sure he did.

Do you think Jim will make better marketing decisions in the future?

Without a doubt. For one thing, when “everyone” says the market will go up or down, Jim will be much more inclined to do the opposite.

December 23, 2020 update: Jim called me this week and told me he was looking to buy a soybean put option in the middle of January when the seasonal trend turns lower on beans. January, March, and May soybean futures are all above $12.60. Yep, Jim really has learned a lot about grain marketing the past year.

Lesson Thirteen: Practical Application of Using Options to Enhance the HTA Price

In early February of 1990, I was contacted by Prospect Farmers Exchange to develop a plan to restore the elevator to profitability. Their accountant had just informed them the co-op had lost money for the first time in its 75-year history. The directors were in shock and embarrassed.

The previous 20+ years, all that was required to make money as a grain elevator in the Corn Belt was to have a lot of storage space and collect 42 cents per bushel to store government-owned grain. In those days, grain storage could be built for about 90 cents per bushel of capacity. Prospect Farmers Exchange had expanded storage capacity to more than a million bushels in the early 1980's.

The USDA announced in December, 1982, the Payment-in-Kind (PIK) program requiring all government grain subsidies and land set-aside payments to farmers to be paid in generic certificates, which were redeemable for government-owned grain at any given day’s current market price. Instead of getting cash subsidies, farmers got government-owned grain to sell for cash.

God enrolled in the PIK program in 1988 with the worst drought in the Corn Belt since 1936. By the spring of 1989, the government-owned grain stocks (biggest part of the carryover) had been reduced from an eleven- months’ worth of use in 1986 to a manageable 70-days' worth of use. Secretary of Agriculture, John Block of Galesburg, Illinois, oversaw implementation of the PIK program, which lowered the cash price of US grains, soybeans, and cotton to what Block called “market clearing levels,” enabling US farm products to be competitive in the world marketplace.

For more than 20 years, this co-op did not need to merchandise any grain and did not even try to buy any grain. The only grain the co-op bought in 1989 was from farmers who needed to transport grain by tractor and wagon and a few loyal co-op members who felt it was their duty to deliver grain to their co-op. Only 79,000 bushels of corn, wheat, and beans had been delivered to the co-op in calendar year 1989. There was not one person among the elevator personnel from gopher putting-out rat poison to the president of the Board of Directors who had the slightest idea of how to attract grain and still make money.

The elevator had the major disadvantage of being a few hundred feet north of the Delaware-Marion county line, which meant their rail freight was seven cents per bushel higher than their nearest competitor a few miles south.

Along with two other consultants, I was contacted by the co-op to develop a plan to restore profitability. After a great deal of research to learn the strengths and weaknesses of the co-op, what the competition was, and what the local farmers needed to increase their profitability, I developed a profitability plan with the center piece being a very unusual grain marketing plan. The co-op manager and his assistant decided I should present my plan to the Board of Directors.

The plan required the co-op open its own hedging account, something they had never done before. I explained a hedge account would allow the co-op to offer marketing tools to grain farmers that would guarantee an average selling price in the top 20% of every year’s price range and above the top of the price range in a normal weather year.

The key to success was the elevator and the farmers had to stick to the plan for each crop year. The profit to the elevator would come from service fees for the various marketing tools which provided a wide variety of price enhancing tools and tremendous flexibility. I assured the board that farmers would only use this plan if they thoroughly understood how the marketing tools worked in up-trending markets, down-trending market, and side-ways markets. I would educate their potential customers if they would get them to come to meetings.

The decision was made to accept my service. Weekly meetings were held at the co-op from early March to the end of April. We adjusted the meeting days to accommodate off-farm work schedules and avoid good weather days in April. The co-op and I did everything possible to educate the famers as quickly as possible before the crops were planted. Some folks attended the same educational seminar three of four times before they were comfortable that they understood how it would work. The education of the co-op’s bank was also a requirement I insisted upon.

We had follow-up meetings with the farmers in July to make sure they understood what had happened and why it happened. The crops were looking good, and the average HTA price was not only 60 cents above the current price, it was above the top price for the year and going higher every day December corn went down. Why?

The cost of corn production in those days was about $2.25 a bushel. The market action in 1990 was pretty normal. The December 1989 futures low the previous fall was below $2.20, and futures began to firm quite steadily into June, just like it usually did. I had recommended to everyone to price 100% of their expected corn production at $2.85 if and when that opportunity presented itself or execute the HTA contracts at whatever price was available at the end of the third week of June, the seasonal high.

December corn traded above $2.85 the second week of June on a normal weather scare. The HTA contracts were filled at $2.85, and orders were placed to buy December $2.60 puts for ten cents. On July 2, December corn traded to $2.96½. The $2.60 puts were bought at 10 cents when December corn traded in the $2.88 to $2.91 area.

Orders were then placed to buy the same number of puts with a strike price thirty cents higher than the strike price of the $2.60 puts, in this case, December $2.90 puts at 10 cents. That first week of July was the classic Corn Belt July 4th week.

It had been dry for three weeks, and the corn market was getting very nervous. Pollination would begin the second week of July and if it did not rain, yield potential would begin to decline. On the afternoon of the 3rd, like always, some weather forecasts were calling for rain after the Fourth of July, and some said no rain was in sight.

We all knew that no rain in sight for Iowa on July 5 meant corn futures would be limit-up on the 5th. If rain was in the forecast for Iowa on the 5th, corn would be limit-down.

On July 3, the farmers across America had to decide to “To sell or not to sell?” But in the community of Prospect, Ohio, on that July 3, there was no stress for Prospect Farmers Exchange customers. They had their HTA price booked at $2.85; they had their December $2.60 puts bought and orders in to buy the December $2.90 puts at 10 cents.

If corn was limit-up on the 5th and 6th, the order to buy the $2.90 puts would be filled. Sooner or later, corn futures would decline and the $2.60 and $2.90 puts would increase in value as prices declined, adding to the $2.85 price of the HTA.

If rain was on the way on July 5, corn would be limit-down with the $2.85 HTA floor locked in and the $2.60 puts would be worth more than they cost. How sweet was that to have 100% of your expected production sold and not care if the futures are limit-up or limit-down on July 5?

On July 5, December corn was down the daily trading limit of 10 cents and down 8 more cents on July 6. By July 23, December corn had traded below $2.50, 48 cents under the July 2nd high.

By the early August, there was a crazy euphoria in the community because of the good crops in the field and the price that the farmers were going to receive for their abundant production. They were going to be paid a relatively high HTA price of $2.85 when the top was $2.96½ plus, every day that corn went down (which it usually does in late July, August, September, and October), the HTA value went up and, lastly, they had 100% of their expected production sold at a great price.

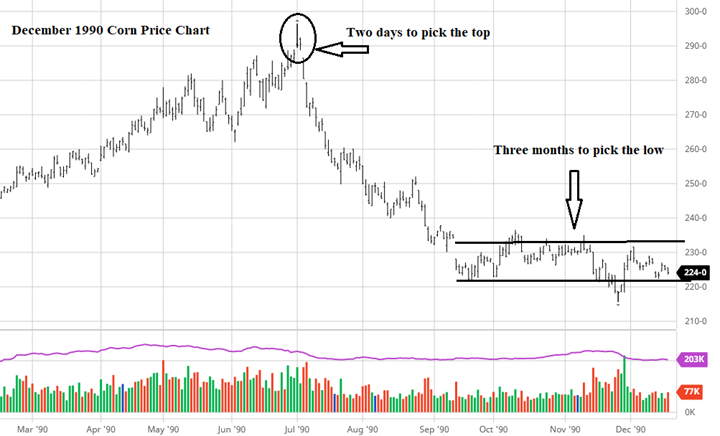

Between September 10 and November 27, December corn traded sideways between $2.36 and $2.16. There was plenty of time to pick a day when futures were near the low for the year to sell the puts at maximum value. Note there were two or three days to pick a price near the top (as usual), but there were three months to pick a price near the low to sell the puts for maximum value.

Those farmers who sold their puts in September and October not only captured the intrinsic value, but also several cents of time value. Those farmers who waited until expiration day to sell the puts sold them for ~48 cents. Most all the puts were sold between 45 and 50 cents. Let’s call it 45 cents.

The cost of the puts was 10 cents. Prospect Farmers Exchange charged a 4-cent service fee per bushel for the puts and no service fee for the HTA (fees for HTA contracts were unheard of in those days).

So, the puts cost the farmers 14 cents each, and they were sold for 45 cents with a net profit on the put transaction of 31 cents. Where did those 31 cents go? They were added to the HTA price of $2.85 to yield a net HTA price of $3.16. What was the top trade of the December corn that year? $2.96½.

What would have happened if a farmer produced only 80% of his expected production?

Prospect Farmers Exchange wrote into the contract those bushels would be rolled to the next crop year for a fee of 4 cents. On November 27, December 1990 corn settled at $2.21 and December 1991 corn settled at $2.59. The December 1990 corn would have been bought at $2.21, and the December 1991 corn would have been sold at $2.59, for a gain of 38 cents. The roll fee of 4 cents came off the 38 cents, so 34 cents would be added to the $2.85 HTA price, putting the 1991 HTA price at $3.19 plus the 31 cents net on the put… $3.50. Again, the cost of production for corn in those days was about $2.25.

Now just think about the possibility for you. Imagine how your life would be changed if you sold 100% of a good crop at a price above the top of the market.

How did Prospect Farmers Exchange handle the 7-cent rail freight advantage of the elevator five miles away? They allowed alternate delivery to any location other than the co-op for 4 cents a bushel. Thus, with the put fee of 4 cents a bushel, they made 8 cents a bushel without handling the corn. It was interesting how many farmers delivered their corn and beans to Prospect Farmers Exchange at a net price lower than they could have received at other delivery locations. It was the farmers’ way to say “Thank You” to their co-op.

After buying less than 80,000 bushels of corn, wheat, and beans in 1989, how many bushels of corn did Prospect Farmers Exchange buy in 1990? It was in excess of 2.3 million bushels. I remind you, the cost of production for corn in those days was about $2.25. Average HTA price on 2.3+ million bushels was above the top of the market on 100% of the farmers’ expected production. December futures contract high was $2.96½.

Lesson Fourteen: Practical Application of Options as an Investment Tool

By 1994, Matt had been a client for 6 years and had become a big user of put options to supplement his HTA price since 1990. He actually put more time into learning about ways to use put options than I had. He had his own trading account, which he used fairly aggressively.

Just as normally happens, December corn had rallied to new highs the third week in June. Matt priced his HTA contracts and got his December puts 30 cents out-of-the-money bought for 10 cents. A couple days later he called me to discuss what I now call outside-the-box marketing.

He asked, “Do you know what the premium is December $2.30 corn puts are?”

I knew December corn was in the $2.70+ range and the market sentiment was still bullish due to the reduced crop from the flood year of 1993.

I replied, “I am guessing those puts are pretty cheap.”

“Yeah, they are three quarters of a cent. What do you think about buying 20 of those puts (100,000 bushels)?”

I said, “Matt, the commission will be as much as the cost of the put!”

“I know that! So what? I will have a cent and a half per bushel invested. What is wrong with that? You said December corn will get to $2.20 if we have normal weather, and we are having normal weather here the third week in June.” I could not disagree with anything he said.

I asked, “Matt, what would be the purpose to buy puts that far out of the money? You are not going to make enough money to make a difference on the pricing of the corn you are growing which is already well-priced.”

“It will be an investment. Everybody says if you can make an annual return of 15% on an investment, you are in tall corn. I expect to double my money. In fact, I expect to more than triple my investment if my market advisor is correct that corn will go to $2.20.” Since I was his market advisor, how could I disagree?

He bought a 100,000 bushels of $2.30 puts that day for 1½ cents per bushel. That was $1,500 total investment risk the third week of June, 1994. How did that work out?

Matt sold those puts for 11 cents per bushel with an additional commission of ¾ cents per bushel. If his market advisor had done a better job of picking the low in December corn futures, Matt would have made 18½ cents per bushel. Nonetheless, his net profit was $8,500. His return on investment was 566% in just four months.

His picture should have been on the cover of Forbes Magazine.

And Finally:

With severe limitations, most merchandisers will allow you to buy, sell, or write options if the options are attached to delivery contract. Most will not advertise it, so you have to ask. Ask for every marketing tool you think will help your marketing program. I have many clients who trade options through their merchandiser.

To trade options without transaction limitations, you will need to open your own futures and options account with a brokerage firm. All option trading accounts can also trade futures; likewise, all futures trading accounts can also trade options because CBOT options are to buy, write, or sell futures contracts.

Note, if you open a futures/options trading account, you never have to trade futures if you only want to trade options. Likewise, you never have to trade options if you only want to trade futures. I have seen that, as people become comfortable with options or futures, they will trade both if the market situation justifies it.

Self Test Questions:

1) If you buy an option, will you ever have a margin call?

2) If you think futures will go down, should you buy a put or call?

3) If you think futures will go up, should you write a put or call?

4) If July wheat futures are at $5.62 on April 30, does a July $5.80 put have any intrinsic value?

5) If July wheat futures are at $5.62 on April 30, is a July $5.80 put in-the-money?

6) If July wheat futures are at $5.62 on April 30, does a July $5.80 put have any time value?

7) What is the strike price of a July $5.80 put?

8) Who has unlimited gain potential after a call option transaction, the buyer or the writer?

9) If July wheat futures lost 10 cents and the July $5.40 put gained 4 cents in value, is the futures price above or below $5.40?

10) What is the delta of the $5.40 put in question 9?

The minimum price contracts offered by grain merchandisers generally use long call options and short futures.

However, a minimum price contract can use, and I think should use, only put options without a futures position.

If you can figure out why I say that, then you really do understand futures and options.

Σχόλια